- Home

- Leslie Parry

Church of Marvels: A Novel Page 2

Church of Marvels: A Novel Read online

Page 2

Sylvan knelt down and placed the baby on the ground, far away from the butcher’s barrels, which were filled with feathers and bones. He stroked her forehead to soothe her, then stood up and jammed his fists into his pockets. He willed his legs to move but they felt like wood. He watched as the folds of the knapsack sagged around her, exposing her naked body to the night air. He bent down and tucked her in again. When she pushed out her tiny fists and batted down the sides, he found the clasps and buckled the sack tightly across her chest. Her body arched and trembled. She opened her mouth and began to cry.

Sylvan felt his throat close and his nose prickle. He took his kerchief from his pocket and dropped it over her face, then grabbed his bucket and shovel and staggered down the gangway to the street, where the slop-wagon was waiting. The other soilers were resting on the curbside among ash heaps and garbage piles, their knapsacks open in their laps. They took draws from water canteens and shared slices of bread, chatted in loud whispers, but Sylvan could still hear the faint cry, raw and tuneless, coming from the yard.

He emptied his bucket over a barrel in the back of the wagon. There was nothing he could do, he told himself. Mr. Everjohn was right. By morning she’d be sleeping alongside a dozen other foundlings in the troughlike crib of the orphanage, nursing Tammany milk. Or some family from the tenement might take her in, raise her as their own. Or perhaps the person who’d left her behind would still come back for her.

Sylvan rubbed his eyes as if trying to make the image stick. Even through the stench of the slop-wagon, he could smell the blood and viscera from the butcher shop. He raised his eyes to the windows above. There could be fifty people living in that building, maybe a hundred. Who would have done such a thing? The baby wasn’t just abandoned to the whims of the city streets—she hadn’t been entrusted to another’s care, or left in a well-traveled place to be discovered and rescued. Sylvan shivered though the night was hot and still. The baby, he knew, was meant to die.

“Broome to Orchard!” the foreman called from down the street, clanking his shovel head against the walk. “Orchard and Broome—step in, hey!”

The other men got to their feet, gathered and readied themselves. Sylvan felt nauseous and light without the sack on his shoulder, without the loot clinking and knocking against his hip. From the yard the wail seemed to come louder. Quietly he slipped out of the stretching, laughing knot of men and ran back down the gangway and into the yard. He stared, breathless, at the small bundle beneath him in the shadows. He knelt down and picked the kerchief off her face. The crying stopped. The baby stared up at him, her eyes glimmering in the darkness.

“Moving out, moving out,” the foreman cried down the road.

Sylvan fell into the back of the line and marched down the street with the others, their caps shoved tight on their heads, their clothes black with grime. They began to sing, as they did every night when they felt their limbs tiring and eyelids pulsing. They moved together like one giant shadow, their bodies low-bent and taut, their shovels striking out a beat in the moonlit dust. The baby slept soundly against Sylvan’s chest, rocking with each long stride. When the band turned on to the main thoroughfare, she kept so quiet that Sylvan thought no one could know she was hidden there among them, except for the brief moment she flashed into view, like a cap of foam on a dark wave, as they rolled through a nimbus of streetlight.

AT THE CORNER he slipped away. He fell back behind the others, hid the baby in his coat. He made his way blindly down the alley—stumbling past wheelbarrows and rabbit hutches, blinking back the drizzle in his eyes. They wouldn’t notice he was gone, not right away—maybe not until they returned to the stable, where the men heeled off their overshoes and scrubbed themselves clean. It was near the end of the shift, he reminded himself. When he reported for work the next evening, he’d say he’d been jumped—maybe by a tough he’d once trounced in an underground match, a fellow fighter hungry for revenge. Would they believe him? Would they even be surprised? Dogboy’s a wild one. He has no people. He’s got no tribe.

He reached his home on Ludlow Street just before dawn. In the yard he placed the baby on a crate and peeled off his sticky shirt. Ducking his head under the spigot of water, he rubbed at his curls and lathered his arms and face with a bar of soap. He gazed at the girl through the falling water and realized he was shaking. Perhaps he could put on Mr. Scarlatta’s brown suit and take her to the convent himself, where blind Sister Margaret taught orphans to make shoelaces.

He filled a bucket with water and carried it down the steps to the cellar door, cradling the baby in his arm. Inside they were greeted by loot from the privies—the rusted door keys and clay pipes, the saucers and belt buckles and green glass bottles—and the few things he’d foraged from the Scarlattas’ glove shop upstairs: a good pair of mittens for winter work, and the dummy hands that now lined the shelves like drowning men reaching for air.

He warmed the water on the stove and poured it into an old washtub. He set the tub, sloshing, on the floor and knelt down beside it. Other than the throaty purr of flies, the room was silent. As he bathed the baby, he saw the red lattice of veins beneath her bluing skin, the tiny claws of her fingernails. She was skinnier than he thought she’d be, with puffed-up eyes and a trail of fuzz down her back, like a wolf pup.

When she was dry, he fashioned a diaper from a rag, then swaddled her in an old tablecloth. From the shelf he retrieved a glass bottle with a rubber hose attached. It had been Frankie’s. He’d been born just over two years ago, heir to the glorious emporium his father dreamed of building: Scarlatta and Son’s Fine Gloves and Handwear. Frankie, with his hammy legs pedaling through the air as if he were riding an invisible bicycle. “An athlete, maybe!” his father cried, tossing him up. “A strongman!”

Sylvan filled the bottle with milk, which he kept cool in a hole in the floor. He pushed the nipple, gnawed and misshapen at the end of the hose, between the baby’s lips. She ate slowly, sluggishly, her skin growing warm against his.

He tried to envision a woman creeping outside to the privy, shaking out the folds of her skirt and watching the baby turn over into the shadows. He tried to picture her posture, the set of her face, the way her moist and terrified eyes would have widened in the dark. But as hard as he tried, the only person he could imagine standing there, stooped over the hole and feeling the bloodstained skirts fall back around her ankles, was a tall woman with wet cheeks and a white kerchief tied around her head. He didn’t know if this woman was a dream or a memory, but it was an image that had been flickering in his mind for as long as he could remember. She was leaning against a wall, crying into her hands. Her shoulders were bunched and heaving, her cheeks half-shadowed and wet. He tried to recall what had happened, who she was—his mother; his nurse? Had she died? Had he wandered away from her in the street? Had she looked up from the fly-spotted flanks of meat at the butcher’s and realized he was no longer at her knee? Or had she, for whatever reason, set him down in front of a Punch and Judy show in the market square, turned on her heel, and walked away?

He didn’t remember much before the age of four or five, when he came to the Scarlattas’—just strange fragments of a life on the street, which clicked through his mind like the framed photographs in a Mutoscope machine. A few months ago he’d gone to a Mutoscope parlor up on the Bowery. He waded through the cavernous room amid a crush of eager, queuing people. It was so crowded he only had the chance to see one strip. He balanced himself on a rickety stool and pressed his face to the cool, slick metal of the eyepiece. He wound the crank slowly at first, so that the pages creaked forward. Each photograph was a little different from the next. Then he spun it so rapidly the pictures whizzed by and turned into a single movement: a boxer knocking out his opponent with a bloodthirsty windmill punch. Slow, then fast. Slow and fast. Separate photographs, then a living story. The boxer’s arm poised behind him, his lips pulled back over his teeth. Then, a few flips later: the opponent’s chin thrust in the air, the muscles in his nec

k twisting, a spray of saliva fanned against the black. Sylvan stood there, alternating between still life and moving image, until his nickel was up and the screen snapped to black.

His early life, he thought, was like the slow flip of photographs: the images were too sparse and sporadic to make any sense together, but each was so vivid that whenever one flickered to his mind, he was startled by its intensity. How could certain visions like these remain so luminous, and yet he had no recollection at all of what had come before or after? A whip-scarred pony, neighing in a leaky stable. A band of red-haired children chasing him down the riverbank, pelting him with rocks. Sleeping in a pile of damp, foul hay. Sleeping in a cedar box on the waterfront. The wood of that box, unpainted and cotton-soft under his cheek, and the sticky sap that dripped from it like a wound. (Mrs. Scarlatta later told him those were the paupers’ coffins, waiting to be filled and taken over the river.) And then this, perhaps the most vivid of all: a square of white cotton blowing down a frosted alleyway. The shape of a hand had been cut out of it. It flapped in the breeze, the missing fingers waving him forward. It tumbled down a set of cellar stairs and landed at a door. He tried the latch, and it opened.

The day Mr. Scarlatta found him hiding in the Ludlow Street cellar, he brought him upstairs to the family’s apartment and crowed, “Look, a stowaway!” Sylvan had heard Mr. Scarlatta recount the story over countless suppers, damp eyes alight with wonder as if seeing it for the first time: “I’d gone down, you see,” he’d begin, rolling his hands in the air as if to coax the story into motion. “A cold, cold morning. There was nothing down there, just a little room of things nobody wanted anymore, not even robbers!” He was proud of the fact he could afford to own things he didn’t use. Some things had come with him and Mrs. Scarlatta from across the sea, and now they had the dignity of occupying their own quarters, too, rather than being turned into firewood for beggars and vagrants. “What I was even looking for that morning—how can I remember?” he’d chuckle, tugging at his whiskers. “But what I should come upon! I go inside—and! Like a little elf had been there. Everything was nice on the shelves! The floor was swept. And this little boy, he was rolled up in a yard of cotton, fast asleep. I was astonished. This little elf”—he lowered his hand to his waist—“just this high, and how did he do all of it?”

Sylvan had been sick and delirious when the Scarlattas found him. For days he slept on a makeshift bed in their apartment—three uneven chairs pushed together—next to a pair of sewing machines. He lay wrapped in that same yard of cotton, shivering and hot, while the treadles tamped out a rhythm beside him, while knitting needles tsked from unseen hands. Once in a while he’d open his eyes and see the flash of scissors, hear the whish of a skirt. Sometimes a hand would slide under his neck and roll his head forward, bringing a saucer of broth to his lips.

As he grew stronger, Mrs. Scarlatta asked him where his mother might be. Sylvan had answered quite plainly that he didn’t have one. She’s dead then? No. She’s left you? No. You’ve run off then, haven’t you? Sylvan, confused, said no once again. When he was able to sit up and move about, she gave him a pair of old shoes, a mended coat, and a polished penny. If he went up the street and bought himself a new set of laces from the convent, she said, he could have a sweet roll when he returned. But the prospect of being out on the snowy street again paralyzed him; he only stared at the penny, red as a burn in his palm. When Mrs. Scarlatta nudged him toward the door, he tried to carry the stained yard of cotton with him, whimpering and clinging, getting tangled up in its train. Finally she took a pair of scissors and cut away the corner. She tucked the square in his pocket, next to the penny. There—just if you get scared—but you won’t, will you?

The cotton, which he had found in a scrap heap in the cellar, had come from a mill in Connecticut. Sylvan & Threadgill, Mr. Scarlatta explained as he rubbed his fingers against the grain—it makes for good church gloves, see? And so this was how Sylvan Threadgill—collective son of the East Side winter, a glove’s carefully scissored outline, and an unlatched basement door—came to Ludlow Street.

After this, the images in Sylvan’s memory came quicker and easier; they joined together in a smooth, whirring story, one he recognized. Mr. Scarlatta kept him clothed and fed in return for daily chores: mopping the stairs, replacing cones of newspaper in the privies, shoveling out the effluent that flooded the yard from the street, washing soot from the windows with a cold wadded rag. He hauled buckets of water up to the tenants, plugged cracks in the walls and floors, brushed ice from the walk in the winters, polished the banister until it gleamed. He made a room for himself in the cellar: sewing his own pillow and stuffing it with newspaper, teaching himself to read those same newspapers, stacked in the corner for kindling; shoveling coal and fixing the stove, boiling his own coffee in a small tin can.

Now the sunlight crept into the cellar, gilding the grime on the high, narrow panes. The baby coughed wetly, rolled her head away. He tried to picture her in the convent’s home for girls: marching in single file under the milky eyes of Sister Margaret, breaking the stale bread that had been donated by parishioners. A life of answering to a false name like Agnes or Claire, pretending to be some other girl in an ill-fitting dress, waiting to emerge from the gloomy, floating world that separated the child she was born as and the free woman she’d become.

Her eyes fluttered open, staring wetly at nothing. A dogboy brought you in when you were no more than a babe, one of the sisters would say. And that’s all I can tell you.

Sylvan knew he would never be able to pass the clapboard wing of the convent, where the orphaned and abandoned girls lived, without craning his neck and imagining what had become of her. He couldn’t see those girls marching down the street—with their powdery complexions and nunlike pinafores and modestly parted hair—without wondering which of them she was. And so she, too, looking for a bearded man in a wrinkled brown suit, would turn her head as they passed on the street. It would be a moment of frightened curiosity when their eyes met: a tremor of recognition, an ache so hollow and lonely in their stomachs that it made them feel faint. They’d find themselves unable to speak, and later, when they turned to look back into the crowd, the apparition would be gone and they’d wonder if they had even seen each other at all.

TWO

WHENEVER SHE WAS SPINNING ON THE WHEEL OF DEATH, Odile tried to focus on one simple and particular thing, like the smell of spun sugar, or the melancholy wheeze of a boardwalk accordion. If her eyes were open, she trained them on Mack’s glinting watch fob while the colors of Coney Island whirled around her. It was a weird calm, when the clamor of the crowd seemed to dull to a whisper and she felt completely still, as if she and the fob were fixed in space, and it was the world that spun madly around them. But today she was having trouble. Her eyes darted through the crowd; her arms strained against their strappings. She felt dizzy and sick. With each revolution of the Wheel, the blood rushed to her head, and so did thoughts of her sister’s letter.

Belle had left home three months ago, in the spring, not long after their mother died. Friendship Willingbird Church, the grand dame of Coney Island, the fabled Tiger Queen of the sideshow, a woman who had survived so much (a Rebel’s bullet, falls from a trapeze, animal bites, and sword slashes) that to have her die so close to home—in a fire, in the very theater that she built—remained unthinkable. Odile still expected to see her in the crowd, swinging her fist to the beat of the cornet, gesturing for her daughter to keep that chin up. She still expected to see Belle every time she walked home after a show—sitting there on the porch railing, smoking a cigarette, her mane of hair loose and wild in the twilight. But Belle was gone now to Manhattan, without explanation or apology. After ten weeks of waiting for a letter, a word—nearly three months of fury and despair—Odile had begun to think the worst. But that morning the postman had left an envelope on the front porch, next to the brass elephant she rubbed for luck every day before the show began. Odile had torn it open as she hurried d

own to the boardwalk.

Odile, I hardly know what to say. I’m sorry for everything. Please don’t be angry with me—I know you must be, and it breaks my heart. I have started this letter so many times, and yet I still cannot summon the words I need. I think of you every minute of the day, and of Mother. I wonder where she is—heaven, yes, but where is that? The sky itself? The ether and stars? Sometimes I imagine it looks like the Church of Marvels, with painted clouds lowered down from the rafters, and glitter fizzing in the air. Sometimes I imagine it is quieter, an undersea cave. I picture her there sometimes, a floating mermaid with a seaweed harp, and the tigers have fins. Then I realize I’ve been sitting too long in the hothouse, staring at the flowers, and the rain is coming down heavy on the glass.

It is hard for me to sleep—sometimes I don’t know what is real and what is imagined. I’m writing this sometime in the night. Who guides my hand across this page, I wonder? Is it I, alert and sound? Is it my dreaming self, compelled to find you in the dark? Is it another spirit? I cannot say. You, dear sister, have always been the brave one, the good one, the strongest of all. Not I. And yet you are me and I am you, and I believe that courage must reside in me, too, though I have yet to find it.

I’m sorry if I was ever short with you, or impatient, or didn’t listen when you tried to confide in me. If for some reason this is the last letter I should write to you, please know that I love you. And you must believe, no matter what, that you are where you belong.

Your Sister

The crowd shrieked and gasped as blades zinged through the air and lodged, humming, next to her ears and above her shoulders. They protested gleefully as Mack snapped on his sequined blindfold and turned his back.

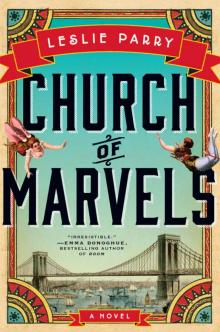

Church of Marvels: A Novel

Church of Marvels: A Novel